NIJMEGEN

Floods and droughts in the upper delta of the Rhine

GUADELOUPE & MARTINIQUE

Extreme weather in combination with

earthquakes in French West Indies

KIEL BAY

Heavy rains and erosion in the Baltic coastal area

VALENCIA REGION

Droughts and agricultural interests in a metropolitan area in Spain

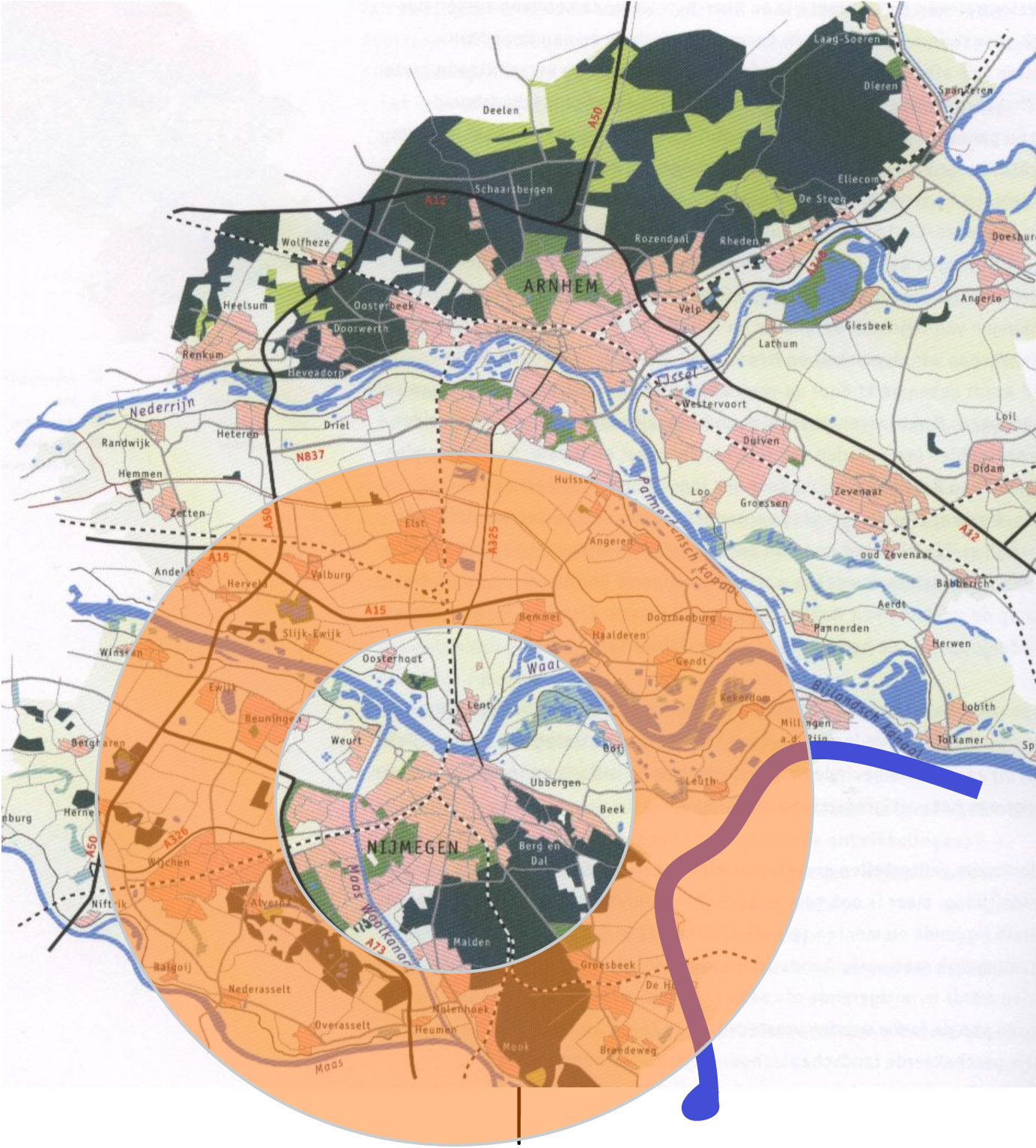

The Dutch city of Nijmegen is becoming well-known because of its planning approach that combines large scale climate adaptation measures with a strong emphasis on spatial quality. Nijmegen is situated along the Waal river, one of Europe’s largest transport and ecological corridors. More than 250M euro has been spent on a new bypass of the Waal, called the Mirror Waal, one of the major urban examples of the Dutch Room for the River project.

This e-zine shows the Mirror Waal project. From awareness of upcoming flooding risks, via complex planning and design efforts into the final result, including innovative ecological engineering, new sport activities and spontaneous festivals.

The e-zine is presented by the INNOVA project. It is the first e-zine out of ten. INNOVA is a research project aiming to facilitate the use of climate data and projections, scientifically known as climate services, in adaptation efforts by urban governments. The project focuses on three European cities, and a small island state. These are: Kiel Bay in Germany, Nijmegen in The Netherlands, Valencia in Spain, and finally, the French West-Indies Islands of Guadeloupe & Martinique.

Photos: Gemeente Nijmegen

Nijmegen, the EU Green Capital 2018

The 170 000 inhabitants of Nijmegen live in the oldest city in the Netherlands, alongside the iconic River Waal. At Nijmegen, it bends sharply to the west, hugging the city and forming a bottleneck in the river. The last major floods of the city in 1993 and 1995 resulted in the action of Dutch Government, the municipality and other stakeholders that created more room for the river, whilst safeguarding the city inhabitants.

The 'Room for the River' project also coincides with urban expansion on the north bank of the river, giving the project a European (nature-development), a National (water safety) and a Local (urban development) focus. The objectives of the project were to achieve climate resilience, future sustainability and spatial quality. With such ambitious and diverging objectives, the Room for the River project had to engage with multiple stakeholders to negotiate mutually beneficial compromises. Besides flood protection the plan was to create opportunities for housing, recreation, culture and nature.

An intensive and substantive cooperation between designers, researchers, citizens and governmental bodies resulted in a city that can now be described as enjoying physical, social and ecological resilience.

The Room for the River project, and the creation of the Mirror Waal demonstrated a paradigm shift in the way we incorporated climate change data and information into decision-making to create an impressive new identity for the city of Nijmegen. This identity as a resilient, safe and sustainable city was one of the reasons Nijmegen was selected (in total on the basis of 12 indicators) as the European Green Capital for 2018. Read more about the nomination and what the jury has said.

Room for the River

The Netherlands is particularly susceptible to a range of climate change impacts. In this low-laying country, climate change will bring about higher average temperatures, more extreme rainfall in shorter periods of time and longer periods of drought. Summers are likely to be drier. As a coastal country, the Netherlands is also affected by the rising sea level. Some of these changes will be gradual, others more intense.

Another major effect of a changing climate is a larger projected volume of water in Dutch rivers. In order to prevent flooding of urban areas, the Dutch government is promoting a policy of widening flood plains of larger rivers. Currently, there are more than 30 such river-widening projects throughout the country. River-widening, rather than raising the dikes, is a departure from the traditional Dutch approach to flood protection. These widening projects along the rivers IJssel, Rhine/Lek, Meuse and Waal are known as creating ‘Room for the River’.

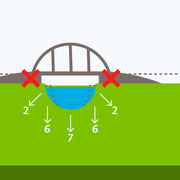

Room for the river Waal along Nijmegen is one of the earliest and completed projects to create greater resilience to climate change. In the case of Nijmegen this involved moving the Waal dike in Lent (northern part of the city) and constructing an ancillary channel in the flood plains, the so called Spiegelwaal (Mirror Waal). This has created an island in the Waal and a unique urban river park with lots of possibilities for recreation, culture, water and nature.

“Telling the story helps us focus”

What narratives have to do with Nijmegen’s Room for the River Program and with Climate Services

Grit Martinez, Ecologic Institute

During dinner at a restaurant at a former Waal docks, first stories about the “Room for the River” program in Nijmegen were shared at the table. I learned that the previous vice mayor of Nijmegen, “a strong don’t argue person from the most influential political party” has been a driving force for the far-reaching activities in Nijmegen. Moreover, Nijmegen seems to hold the nick-name “Havana of the Waal”, which indicates a rather liberal political attitude in town. “People took a lot of time to understand what the river wants, how it works,” a member of the dinner gathering remarks. When we arrive at our lodgings - the 1885 constructed vessel “Opoe Sientje”, which now exists as an atmospheric museum and boat hotel in the Waal harbour of Nijmegen - we meet its owner, Leon Berkers. Leon is a key player behind numerous festivals and other events along the Waal. He leaves no room for doubt that we need to live in tune with the water instead of mastering it; however, “this does not mean we cannot enjoy it”, he says.

"we need to live in tune with the water instead of mastering it"

On the next morning, we continued our investigations, meeting with the engineers and land-scape planners responsible for Nijmegen’s Waal solution. Our aim was to understand the process that resulted in the wisdom of allowing the water to enter Nijmegen, while protecting it from its destructive forces. The experts told us that climate-related data and other information were a vital component in making the decision to move the former Waal dyke and construct an ancillary channel in the flood plains.

“the story behind the data is more important than the data itself”

Nevertheless, they also emphasized that, “the story behind the data is more important than the data itself”. Understanding the perspectives and needs to enable innovative solutions requires situational and problem analysis that take cognizance of the interests of different stakeholder groups. Initiated by the national government, the execution of Nijmegen’s “Room for the River” program was a community-led process in which local desires for water safety met national mandates for coupling flood protection with spatial quality.

Last, but not least, data and other information unfolded their powerful forces only on the grounds of historically grown convictions and entrepreneurial visions. The many tourism and recreational businesses emerging from the “Room for the River” program - which we visited after the meeting on a bike tour along the Waal - document this perfectly.

Since the Dutch have demonstrated the ability to stay ahead of their river flood problems, we wondered how national and local levels prepare for those climatic changes that tend not to be a typical Dutch domain, culturally speaking. These include potential heat stress and droughts, increase in water and air temperatures. Could climate data and other information inform new cycles of adaptive policy programs in the Netherlands and elsewhere? In the INNOVA project, we have just started to investigate how and which climate related services could be beneficial products in the specific societal contexts of the INNOVA hubs in the Netherlands and in Germany, Spain and France.

Grit Martinez is an environmental historian and economist. Her research examines socio-cultural dimensions of climate governance. She works in interdisciplinary contexts across the borders of the humanities, social and natural sciences and engineering.

Room for the Waal

a new riverpark for nijmegen

Copyright: Gemeente Nijmegen

The use of this unique River Park.

The Urban Climate Adaptation Ezine is a newsletter of the INNOVA project. INNOVA is an EU research project aiming to develop innovative services for local challenges relating to climate change. A “climate service”, in simple terms, is a process or (set of) tools that brings climate change data and information to decision- or policy-makers. The climate information is presented in a way that makes sense to these users, is specific for their unique problem, and is easy to incorporate into their own work processes. Climate projections, which are simulations of possible future climate based on the scenarios of greenhouse gases, is normally the key element of climate services.

INNOVA aims to show how climate services can support the adaptation efforts of three European cities, and a small island state. These are: Kiel Bay in Germany, Nijmegen in The Netherlands, Valencia in Spain, and finally, the French West-Indies Islands of Guadeloupe & Martinique. These locations are so called “innovation hubs” and are the testing ground for the development of climate services for specific and local issues related to climate change impacts. These four hubs are also generally representative of many other local areas and issues around the globe.

They connect adaptation to climate change with local economic development, city planning and many other real-world issues. INNOVA values social alongside that of scientific innovation and the needs and ultimate benefit of the stakeholders are at the heart of the project.

In this first Ezine we introduce the Nijmegen hub of the INNOVA project. In subsequent issues we will introduce the remaining hubs, each with its own societal context, perspectives and climate change impacts. These Ezines will also explore topics related to climate projections, adaptation, how climate services are developed, amongst others. Importantly, the Ezines will present the progress and findings of the INNOVA project in a way that is easy to understand.

INNOVA is funded by the EU Programme entitled ERA4CS.